With its distinctive blue color and use of gold and silver ink for the script, this page can be readily identified as part of a manuscript known as the Blue Qur’an, which is dispersed among severa...

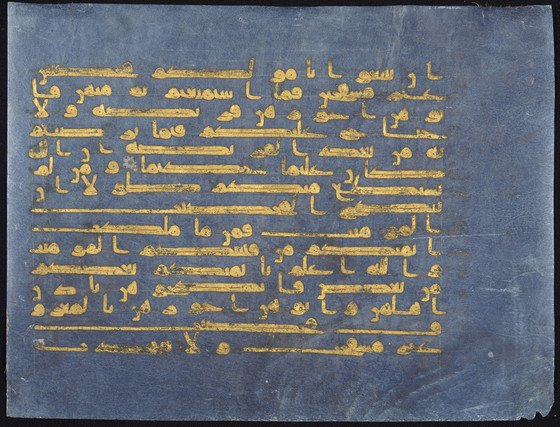

With its distinctive blue color and use of gold and silver ink for the script, this page can be readily identified as part of a manuscript known as the Blue Qur’an, which is dispersed among several collections in North America, Europe, and the Middle East but survives primarily in Tunisia, where it was probably made. While this Qur’an is unique among Islamic manuscripts due to its coloration, it shares similarities with Byzantine bibles and imperial edits that used purple parchment with metallic inks. Silver rosettes (now tarnished) separate each verse, which once added further luminosity to contrast the deep blue of the page. The scribe took care to elongate several letters in each verse, effectively justifying the margins of the text block. As with many early Qur’ans, the Kufic script here does not feature dots or diacritics. Nor would its reader have necessarily needed such markers to recognize the verses before them since many worshippers learned verses by oral transmission and memorization.

Only a small number of Qur’ans on colored vellum survive from the medieval period. This manuscript, however, also marks one of the most sumptuous Qur’ans ever produced, thanks to two exceptional features combined in its folios: continuous writing in gold (chrysography), and its remarkable blue parchment, both of which have sparked numerous debates regarding the production methods of their artists. While many scholars initially believed that the blue parchment was dyed, recent studies have achieved results similar to surviving folios with brushed indigo. As for its radiant ink, some believe that illuminators formulated the ink from powdered gold suspended in solution, as described in the eleventh-century manual on calligraphy by Muʿizz ibn Bādīs (d. 1061), then outlined the text in reddish-brown ink. However, the vast quantities of powdered gold needed, along with the opacity and current cracking of the text, have led others to posit that gold leaf was applied to letters formed with gum Arabic or another adhesive.

From its material traits, this folio once belonged to a manuscript that was originally around 650 folios in length, likely divided into seven-volumes. Numerous scholars have hypothesized the origins of this codex covering Andalusian patronage, to that of Fatimid or Abbasid caliphs, among others. Given the luxurious materials required for its production, this manuscript required no less than a royal patron, whose illustrious workshop was well-versed in the visual codes of prestige of their imperial competitors. A Qur’an matching this description also survives in the inventory records of the library at the Great Mosque of Qayrawan from 1294, though it is difficult to verify if it is the same codex.

More...